MINOR KEYS

In previous units, every diatonic collection and its key signature have been associated with only one tonic, and all scales have had the same intervals between their scale degrees. This chapter shows that tonic and collection can be changed independently, which results in different modes.

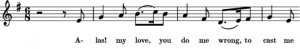

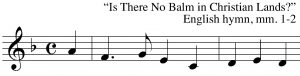

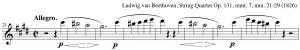

In Unit 6, you learned about (and memorized) the relationships between key signatures and major keys. You associated each diatonic collection (the pitches given by a key signature) with a single pitch that — when it’s the tonic — results in a major key. But a second pitch within each diatonic collection may alternatively serve as a tonic. Consider the following melody:

While the notes and key signature look like G major, the pitch E seems more central to the melody. Listen to this phrase: not only will G not seem like “home,” but the melody will feel darker than the major melodies we’ve worked with so far.

In the one-sharp collection, given by the key signature, this new tonic (E) lies a minor third below (or a major sixth above) the major tonic (G). This new tonic is called the MINOR TONIC. The names major and minor are ways of referring to two different tonicizations within a diatonic collection. These two types of tonicization are called MODES — major mode and minor mode. From now on, we will name keys using their tonic and mode, in that order. Thus, we would say that the excerpt above is in “E minor.”

The first video below discusses “minor” in terms of the “modes,” a concept we’ll return to in Unit 14. The second video then discusses some specific minor-mode concepts.

Relative Keys

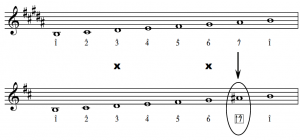

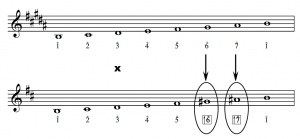

Every diatonic collection contains one major tonic and one minor tonic. Any two keys that share the same key signature are called RELATIVE KEYS (also called RELATIVE MODES). Here are the scales from two relative keys—C major and A minor—written so you can see the different placement of their scale degrees within the same diatonic collection:

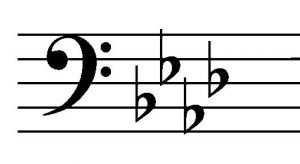

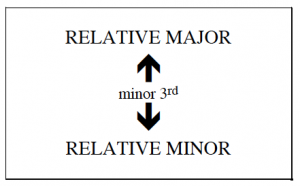

Since every diatonic collection can be used for two relative keys, you must now also memorize fifteen minor key signatures in addition to the fifteen major key signatures you memorized in Unit 6. Fortunately, since the minor tonic always lies a minor third below the major tonic within any one key signature, you can use your knowledge of the major key signatures to determine their minor counterparts. For example, consider the following key signature:

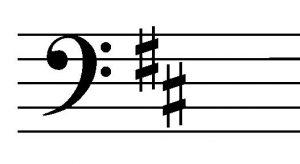

In unit 6, we learned that this key signature (and hence its diatonic collection) is associated with the key of Af major. In other words, if the pitch A flat is tonicized within a four-flat diatonic collection then the resulting key will be Af major. To calculate the minor tonic within that collection, simply count down a minor third below Af. The resulting pitch is F. Therefore, the minor tonic in the four-flat collection is F, and the key signature above also represents F minor. We can put this relationship in general terms: To determine the minor tonic for a given key signature, find the pitch a minor third below the major tonic. This relative-key process is also helpful in reverse — to determine the key signature when given a minor tonic. For example, if given the minor tonic of B, you must first count up a minor third to its relative major — D. Since they share the same key signature, the key signature for B minor is the same as that for D major:

We can put this relationship in general terms, too: To determine the key signature of a particular minor key, count up a minor third to its relative major, which shares the same key signature. This small chart will help you to remember the relationship between relative major and minor keys:

And here is the circle-of-fifths arrangement of the keys, with the major keys written around the outside of the circle and their relative minor keys written on the inside:

Parallel Keys

There is another way of comparing major and minor keys. Whereas relative keys share the same key signature, we can also compare keys that share the same tonic. Look at the following two excerpts, which come from two different spots in Mozart’s 41st Symphony:

Comparing these two short excerpts, we see that the first uses the no-sharp/noflat collection; the second uses the three-flat collection. The first is in C major; the second is in C minor. Keys that use different diatonic collections but share the same tonic are called PARALLEL KEYS (also called PARALLEL MODES). It is helpful to compare scale degrees in parallel major and minor keys:

Note that scale degrees1, 2, 4 and 5 are the same in both modes. However, scale degrees 3, 6, and 7 are each a half-step lower in the minor mode when compared to the major mode. This is true of all parallel major and minor keys.

For convenience, it’s usually easiest to write out music in the minor mode not with accidentals (as in the parallel scales above), but with a key signature instead:

Although scale degrees 3, 6, and 7 in the minor mode are lower in comparison to the parallel major, they are nonetheless still diatonic pitches because they are a result of the different diatonic collection used for the minor mode (as shown by the key signature). Parallel major and minor keys share the same tonic, and all their corresponding scale degrees share similar functions.

The Importance of the Leading Tone

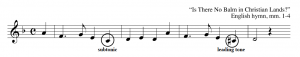

One often-used way to make someone hear a note as tonic is through the half-step relationship between the tonic and leading tone. Therefore, an emphasis on two pitches a half step apart can tend to make the higher of the two pitches feel like a tonic. Consider the first four measures of the following excerpt:

Although the first four measures of this excerpt lack both tonic-dominant and tonic-mediant relationships, the strong emphasis on the D–Cs relationship tends to give D a feeling of centricity even before the music proceeds any further. Indeed, the Cs (scale degree &) exerts a strong sense of leading towards the D (scale degree !). This feeling of leading to the tonic has given rise to a special name for any seventh scale degree that lies one half step below the tonic: the LEADING TONE.

In the major mode, the leading tone occurs naturally: The seventh scale degree in major is diatonically one half step below the tonic. In the major mode, all seventh scale degrees are leading tones.

But in the minor mode, the seventh scale degree occurs diatonically one whole step below the tonic. Here is a shot excerpt in D minor:

The tonic in the above passage is D. It is created through the relationships among A (the dominant) , F (the mediant), and D (the tonic). There is no leading tone in this passage, because the pitch C is a whole step below the tonic. (A pitch one whole step below the tonic is often called the SUBTONIC.) Now look at how that passage continues:

In m. 3, the C has been raised to Cs, bringing it to within only a half step of D. This creates a leading tone where, diatonically, there was none. We call this kind of non-diatonic pitch CHROMATIC — an alteration from the prevailing key signature. Any leading tone, when emphasized in various ways, tends to strengthen the tonic feel of the pitch above it. But a chromatic leading tone (such as the Cs above) can engender particularly strong feelings of leading towards the tonic.

We have now examined three pitches whose relationships with the tonic serve to establish its feeling of finality: the dominant, mediant, and leading tone. The relationships between these pitches and the tonic may work independently or in conjunction with one another. A passage might contain only one, or it might contain two, or all three relationships. The extent and strength of each relationship are what determines the strength of feeling of the tonic.

Three Forms of the Minor Scale

The diatonic form of the minor scale is often called the NATURAL MINOR scale. Here’s an example of a passage that conforms to the natural minor scale. Note how all pitches (including 6 and 7) are unaltered from the key signature, and therefore diatonic:

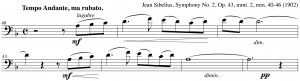

If we borrow the leading tone A sharp from B major into B minor, we will have transformed the subtonic into the leading tone. In doing so, we have created the B HARMONIC MINOR scale:

The Xs still mark the remaining difference between scale degrees in the two parallel modes, but the arrow now points out the borrowing of the leading tone from the major mode into the parallel minor, and the leading tone is highlighted to indicate that it is a borrowed, chromatic pitch. Here is an excerpt that conforms to the harmonic minor scale. Note how the seventh scale degree is consistently raised to function as a leading tone (B sharp):

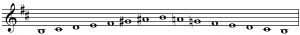

Sometimes, both 6 and 7 are borrowed from the major into the parallel minor. This often occurs in scalar passages moving up from 5 to 1. If we raise 6 and 7, we have created the ascending form of the MELODIC MINOR scale:

This makes 3 the only pitch that is different between the two parallel scales (marked with the X). The two arrows point out where both 6 and 7 have been borrowed from minor into major, and these two chromatically altered scale degrees have also been highlighted to emphasize this. The melodic minor scale has — by convention — a different form when descending: it reverts to the natural form. Thus, the complete B melodic minor scale looks like this:

Here is an excerpt that conforms to the melodic minor scale. Note how the sixth and seventh scale degrees are presented in their diatonic forms (D and E) at the very beginning when the music is descending, but are chromatically raised (to D sharp and E sharp) when the music is ascending during the rest of the excerpt:

Keep in mind that only the melodic minor scale has different ascending and descending forms. The natural and harmonic forms of the minor scale stay the same regardless of whether they are ascending or descending.

Determining if Music is in Major or Minor Mode

Any given key signature can represent two different keys — one major and one minor. So how can you tell, just from looking at any piece of music, just which key it’s in? There is an old music-teacher aphorism that says, “Look at the last note.” There are indeed many pieces of music that end on the tonic, so you might think looking to the last note for guidance would be helpful. For example, look at the following folk song:

The four-sharp key signature may represent either E major or Cs minor. To determine which of those two keys this song is in, you could “look at the last note” — which is Cs — and end up with the right answer. Looking at the last note can often be a useful, expedient clue about what pitch might be the tonic, but you cannot always rely on it. There are several reasons why you should examine more than the last note when trying to determine the mode of a piece or excerpt. First, you should be aware that some pieces (but not many) don’t end on the tonic. For example, here’s the end of a movement from a violin sonata by Arcangelo Corelli:

The movement has a two-sharp key signature, which could serve for either D major or B minor. The movement ends on Fs, which is neither D nor B, so that note alone is insufficient to tell you the key of this movement. But if you look earlier you’ll see Fs and B in a dominant-tonic relationship, coupled with the use of the leading-tone As, all of which makes us hear B (and not D) as the tonic in this movement. Second, there are quite a few excerpts (not complete movements) that don’t end on the tonic. Just because you’re not seeing the entire composition or movement doesn’t mean you would unable to determine the mode. For example, consider the following excerpt from a trio by the nineteenth-century composer, Louise Farrenc:

This eight-measure phrase ends on F sharp, which offers you no clue about whether Farrenc used the one-sharp signature here for G major or E minor. Instead, you should look at the pitches throughout the phrase, which exhibit dominant-tonic (B–E), mediant-tonic (G–E), and leading-tone-tonic (D sharp–E) relationships, all pointing towards E as the tonic in this phrase. If you ponder all this, it raises an important epistemological issue: If the last note were the only factor that leads us to the tonic, then we would always be listening to music in a tonality-free fog — clueless about whether any piece is in major or minor mode until the very last pitch is sounded. But we know this is not true. When we hear tonal music, we begin to hear it in one key or another almost immediately, inferring the tonic in a process that starts with the first pitches we hear and continues dynamically as we attend to the various relationships among the pitches. When you look at tonal music, you should imitate this same process with your eyes, asking what factors contribute to tonicizing which pitch from the outset.

Hearing the difference between major and minor

Why would composers use major keys instead of minor keys, or minor keys instead of major keys? It’s because both modes have a very different effect. Major keys tend to be brighter, and tend to draw out happier, resilient, and more positive feelings. Minor keys tend to sound darker, and tend to draw out more contemplative, melancholic, and more negative feelings. Consider this minor version of “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun.” The prototype version (by Cyndi Lauper) is a bright and poppy song, while converting the song into minor changes the tone completely.

In fact, there is something of a cottage industry around changing major mode pop tunes into minor, and vice versa. Here’s a VICE story about it.

Finally, here’s a video where people take horror-movie themes (which, unsurprisingly, are frequently in minor) and change them into major: